Cooperative to the Core - A Yearling's Guide to Thermal Traffic

In this post...

The following is a continuation of our Yearling Notes series and an excerpt from the May/ June 2018 of USHPA Pilot Magazine.

Cooperative to the Core - A Yearling's Guide to Thermal Traffic

By Calef Letorney

A gaggle at the start of the Pan-American Championship in Brazil. Photo by Nick Greece.

I vividly remember the first time I joined another pilot in a thermal. It did not go well. The day ended with beers in the LZ, so it could have been much worse... but Rosco had spun his glider avoiding me and he wasn’t happy about it. Everybody (but me) thought it was entirely my fault. While arguing my defense, I learned two valuable lessons: First, as long as I was explaining my perspective I was investing my energy in justifying my mistakes (complete waste of time) when I should have been focused on learning. And second, I had a lot to learn.

Fast forward 13 years, and I now have the pleasure/responsibility of teaching novice pilots how to soar and navigate traffic. This lesson on thermaling cooperatively is a mashup of tips I’ve gotten from other pilots, with some of my own ideas sprinkled on top. To make this article appeal to a wide audience, I’ll begin with the basics and work up to advanced techniques. Let’s start by reviewing the ground rules, known as right-of-way. For expediency, we’re only going to cover thermal rules, but it’s your responsibility to understand them all.

Thermal Right-of-Ways

1. The first pilot in the thermal sets the turn direction. When joining, you must turn the same direction as pilots already established in the thermal.

2. Pilots in the thermal have the right of way over pilots joining the thermal. This means that if you’re in the thermal, it’s your prerogative (and I would argue responsibility) to fly the pattern that maximizes your climb rate. Everybody wins when the joining pilot fits into the pattern of pilots climbing fast.

3. The lower pilot has the right of way because the wing obscures upward vision.

4. The fastest climbing pilot has the right of way. In some places this is a rule, other places it is a courtesy; regardless, this is a natural extension of #3. This rule is logical and productive as we want the fastest climber defining the pattern of the thermal (location, size, shape, direction) so we can all benefit. Be careful when claiming this right of way, especially if the pilots above you have just reached an inversion and are “bumping against the lid.”

As you can see, the right-of-way rules are pretty sparse and provide minimal guidance, so here’s my additional instruction:

General Advice

1. Right-of-way does not mean much if you get injured or die in a mid-air collision or crash into terrain avoiding said collision. Regardless of who has the right of way, it is always your responsibility to identify and avoid collision courses well before they materialize.

2. Thermaling in a gaggle is optional. If you’re not comfortable, you’re not having fun, so don’t do it. No thermal is worth risking a mid-air collision for, so if you don’t feel confident and comfortable, seek less crowded airspace.

3. Put your head on a swivel, and predict the future. It’s your job to avoid potential conflicts. Continuously scan the sky in all directions. Your goal is to understand the vector of travel of the other wings and predict their likely next moves, so you can “pilot ahead of the situation.”

4. Make moves early and gradual. This one comes from Tom Lanning, who says “It is much easier to match speed and course if it is done over a long period. Pilots should watch a gaggle and plan their entry far away. Start making adjustments early so corrections are smooth and minor. This also allows the entering pilot to see where the better lift might be.”

5. Assume other pilots do not see you and will not yield. Even if a pilot appears to be looking right at you, don’t take anything for granted. Don’t assume they understand the situation (and who has right of way!) the same way as you do.

6. It only takes one stray pilot to cause a problem. Whether it’s a gaggle of 75 or 2, it only takes one pilot to blow up the whole thing. Don’t be that pilot.

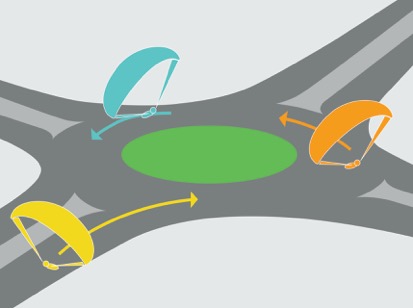

Illustration 1

7. Communicate early and often. If you think somebody does not see you or is acting a fool, don’t hesitate to shout or whistle.

“Put your head on a swivel, and predict the future. It’s your job to avoid potential conflicts.”

8. See the roundabout. I like to visualize a gaggle in a thermal as cars in a roundabout (Illustration 1). Flying in a thermal is much more complicated as the size and location of the roundabout constantly change, but the roundabout analogy provides guidance on how to interact with traffic.

9. “Turn direction” only applies once you are in the thermal. Getting into the thermal, turn whatever direction is necessary to gracefully merge into the roundabout.

10. Speed matters. When you have gliders flying at different speeds, thermal traffic can be harder to judge. The two factors are how fast the pilot is flying and what the pilot is flying. There is a big difference between training gliders and comp gliders, but a bigger difference between paragliders, hang gliders, and sailplanes. It generally makes sense for the slowest aircraft to fly on the inside of the roundabout with the faster aircraft flying large diameter turns around the outside. It’s no problem to have paragliders, hang gliders, and sailplanes all in the same thermal, but you do need to pay a bit more attention and factor in the speed differential.

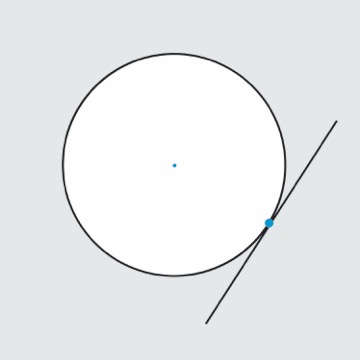

Illustration 2

11. It’s the ground that hurts. Watching the traffic is good, but never forget your proximity to terrain. Remember that your escape routes go way down and consequences for failure go way up when you’re adjacent to terrain, so give yourself extra margin for error.

12. All bets are off in mixed lift. Be especially mindful of the complex situation when you have thermal traffic interacting with ridge traffic. It is easy to have conflicts when some pilots are following ridge rules while other pilots are thermaling.

Entering the Roundabout

Illustration 2b

1. Always approach the roundabout on a tangent. A tangent is a continuous line that intercepts a circle in precisely one place, which can only happen if it touches just the very edge (Illustration 2). This sounds simple, but anything less than a tangent has two potential points of conflict (Illustration 2B).

Illustration 3

2. You often need to turn the wrong way to enter on a tangent. Huh? Consider this example: When driving in the USA, what does your steering wheel do as you enter a roundabout? You turn your wheels to the right (opposite of turn direction), which lines you up to enter the circle on a tangent (Illustration 3 at point 1). You only start turning left once you are already in the roundabout (Illustration 3 at point 2). The same is often true of entering a thermal. Once you have identified the thermal roundabout, start heading towards the tangent of the circle as early as possible. This involves the least dramatic turns (most efficient for you) and reduces stress for those who are already in the roundabout Note that if you are entirely to the left side of a right turn thermal, or right side of a left turn thermal, you need not do this opposite turn. You can just do a steadily decreasing radius turn until you come in on the tangent (Illustration 4).

Illustration 4

3. Signal your intention to yield. There’s often uncertainty whether a merging pilot will join before or after a pilot who is already going around the thermal. Remember, it is the uncertainty that causes issues, so yielding only works if you make your intentions clear early. If there’s any ambiguity, the merging pilot should indicate the intention to yield by over exaggerating a turn towards (or even past) the tangent (Illustration 5, point 1). After this signal, the joining pilot could pull in behind the pilot in the thermal, following his path (Illustration 5, path A). As always, make these moves early, so your intentions are clear and the other pilots have time to react. If you’re on the opposite end of this situation (established in the thermal, wondering what the joining pilot is going to do) you may choose to create more room by turning a little earlier so you are clearly in front of the joining pilot. Alternatively, you can invite the joining pilot to merge in front of you by briefly rolling out of the turn, showing the pilot there is room to merge in.

4. Make additional lanes: When there is no break in traffic for us to merge in, we can’t just hit the brakes and come to a stop like we would in a car. So what do we do? We add lanes to the roundabout. Sometimes the outside lanes are still in lift, but other times it is necessary to fly around the outside of the lift, waiting for the opportunity to merge into the rising air (Illustration 5, Path B).

Flying the Roundabout

1. Fly the pattern. When thermaling, if you don’t have a well-informed reason to go off on a lark (such as a suspicion of stronger lift nearby), then just fly the pattern.

2. Focus on active flying. Actively manage your pitch to minimize canopy movements and keep your glider flying as efficiently as possible. Be especially mindful of the inputs you give to your outside wingtip. Active flying will help keep your bagwing inflated, which is crucial as few things blow up a gaggle quite like a pilot taking a collapse and losing directional control.

Illustration 5

3. Place yourself in traffic. Once in the thermal, adjust the size and shape of your circles to give yourself space.

4. The passing lane is on the inside. I am often frustrated by a wide roundabout that misses the core. Yes, flatter turns have a lower sink-rate, but when there’s a strong core, efficiency be damned, you want to grab onto that rocket ship. If the roundabout is wide enough for me to establish an inner lane that doesn’t cut anybody off, I’ll merge into the middle. There’s nothing discourteous about this move, but it can be as intimidating as it is productive. The inside lane gets scarier in bigger crowds, with less experienced pilots, and when pilots are flying aggressively. Keep an eye out for rookies who wander out of the lift, realize the mistake, then turn tighter into the lift not realizing you are on the inside. Remember, with no quick exit, the inside lane can get dangerous quickly. But having properly warned of the dangers, I must say that I’ve had so many good experiences in the passing lane, that I fully recommend you use this move when it feels right. This is the move that enables you to pass the gaggle, punch through the inversion, and get 1500’ higher than anybody else. Booya! Just keep an eye on the pilots around you, watch the exits, and be ready to bail if there is anything you don’t like.

The author working above his friends.

5. Know when to cut people off. Occasionally you will find yourself following another pilot around the traffic circle thinking, “OVER THERE, the best lift is over there!” In the following position it can be really hard to correct the shape and location of the circle, so it can be best to “take a pass.”

To pass the pilot, tighten your turn during the downwind portion of the roundabout to cut across the middle of the circle. You goal is to come out in front of the other pilot and guide the pilot to the better lift. Taking a pass is a high-level maneuver that smells a lot like cutting off the other pilot, but when it’s done right, everybody smiles. Be careful not to take a pass in the broken bubbles of thermals we often get with high pressure as it can often result in no improvement in climb rate, which just serves to increase stress levels. Remember, the point of this move is to relocate the circle for everybody’s benefit, not for you to momentarily dip a wingtip in stronger lift at the expense of others. Use this technique sparingly and only when the juice is definitely worth the squeeze. Otherwise, you’re just flying like a jerk.

6. Know when to flatten out. Flattening out is the opposite of taking a pass, but serves the same purpose of adjusting the roundabout to better suit the thermal. Think of flattening out as a foraging party, a hopeful mission where you roll out of the roundabout to explore potentially better lift. Leave from the outside lane without cutting anybody off and this is not an aggressive move, so you can try it as often as you want. We use this move because thermals can be snakey creatures and our roundabouts need to follow suit. Just watch a bird—they flatten out all the time. This technique is especially useful as you transition between air masses with different wind vectors. To recognize when you want to flatten out, watch your ground track and feel your harness. You will see and feel yourself being drawn towards stronger lift. If the lift keeps getting better, keep flying straight and try to feel where the thermal is drawing you. You might fly straight for only 25’ or you could fly straight for 300’ and get sucked into the mothership. How far you have flown straight impacts whether you’re still going to be in the same roundabout or if you have room to start your own roundabout. Be mindful of the traffic as you may need to yield to your original thermal.

Thermaling in traffic can be a bit daunting at first, but once you get the hang of it most pilots come to really enjoy gaggle flying. Like anything else, you should work up to the more challenging situations cautiously. There’s bound to be confusion and occasionally disagreements. Don’t let this faze you. Just be sure to avoid collision and if you can, find the pilot later to have a friendly discussion about what happened. This is all part of the learning process, so if you’re a new pilot be open-minded to criticism. And if you’re the more experienced pilot that nearly got run over by a rookie, take some time to educate the next generation; I’m sure glad Rosco and the gang schooled me all those years ago!